- Home

- Planet Wine Blog

- To the Ends of the Earth

To the Ends of the Earth

Posted by on

I have been working in the wine industry for over 30 years, and have been somewhat cynical about natural wines, the many still-fermenting ‘Pet-Nats’ with their fancy labels, high prices and, at times, unimpressive liquids

concocted by bearded hipsters.

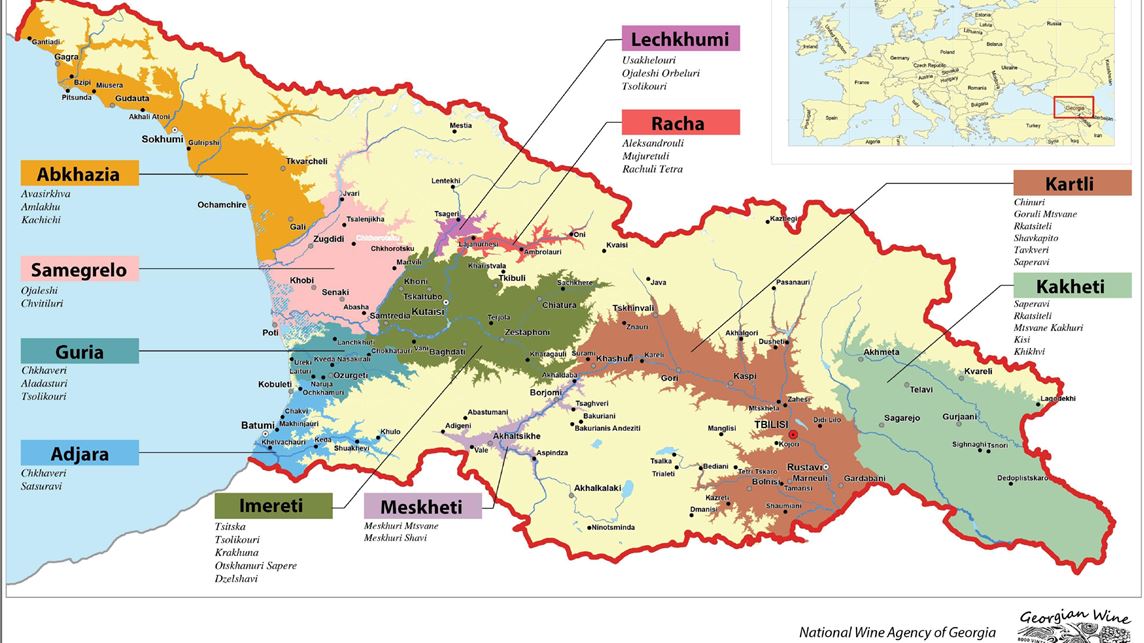

Now let me step back 8000 years: this is when Georgia (Eastern Europe, not US Coca-Cola country) started producing wine naturally. Georgian wines have always (and still are to a large extent) been made using natural yeasts occurring in the vineyard, and without chemical sprays or the addition of SO2.

In 2017, an invitation from a school friend to join him on his hunt for his father’s ancestral home in the Ukraine had me poring over maps of the Black Sea and beyond. Immediately, my tendrils were out, feeling for wine connections in Georgia and Armenia.

After a week in the Ukraine, including a

day-trip exploring Chernobyl, I landed in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia.

Despite a midnight arrival, the suited driver of the Ararat Cognac Factory was

there to greet me, guiding me to the large black Mercedes and my rather tacky

AirBnB accommodation with raised eyebrows.The following day, we drove to the

‘factory’.

Fifty year old Ararat Cognac in hand

While the

facilities, with views of Mount Ararat in Turkey, were certainly outdated

(read: dilapidated), their very valuable assets are the multitude of barrels of

liquid they have in stock. Armenian ‘cognac’ is highly regarded around the

world and especially in Russia.

The tasting was held in a large wood-paneled room with high ceilings and naïve paintings of the owner leading worker brothers to shore. ‘Rustic’ would be a good descriptor for the surroundings, as well as the ageing chocolates that were proffered.

As the sun set with Mt.Ararat in the distance, a gifted bottle of 50-year-old Ararat cognac in my hand, I resolved to import some of their products. Good products, good people.

That

evening, back in the capital Yerevan, I went in search of a wine bar called

Wine Republic. It turned out to be a Thai restaurant with an excellent wine

list and cellar. The young staff were friendly and led me through an

interesting array of Armenian wines made of indigenous and ‘Georgian’ grape

varieties such as areni noir, saperavi, and kisi.

Yerevan to Tbilisi by marshrutka to meet the qvevri

And now to Georgia, the country where wine has been made for 8,000 years! I travelled from Yerevan to Tbilisi in a marshrutka, a small bus certified to carry up to 16 passengers.

After being

stopped for a speeding offence, we arrived in the hilly capital of Tbilisi, which is much

more focused on tourism than Yerevan. Wine is the engine of this country, and

every fourth store is a wine shop, wine bar or restaurant. After a night of

walking and enjoying a large steak and some local red wine, I was picked up in

the morning by my translator Salomé, and a driver. This was the beginning of a

4.5 day, 22-winery whirlwind tour of Georgian wineries that had been arranged by the Georgian wine marketing agency.

Day one ended with visits to the residential wineries of three brothers, each trying to outdo the other. I remember much food, many toasts and some singing, but no dancing.Very friendly and hospitable people, the Georgians!The following days were a blur of wineries, qvevri and vineyards. Wineries ranged from small to foreign-owned and large corporates. Most of the wineries work with autochthonous varieties like mtsvane, rkatsiteli, saperavi, kisi, chinuri and 500+ others.

More qvevri and some chacha

Of the 22 wineries I visited, having tasted around 150 wines, I will eventually work with 4 to 6. As in any other winemaking country, vintners are usually driven by passion.The winemakers I like to work with are those who love what they do and who will give up much to achieve their dream.

A prime example of this kind of winemaker is John Wurdeman of Pheasant’s Tears winery, named after a Georgian fable in which only the best wines will make a Pheasant cry. John grew up with hippy parents in California, and then decided to study painting in Moscow. He visited Georgia in 1996, met and married his wife, Gela, from a winemaking family, and stayed.

His wines are the most well known from Georgia, possibly because of his western roots and connections. They are all made in qvevri. The skin contact varies with each grape variety.

The skin and

stalks floating on top of the wine are called chacha, also the name for

Georgian grappa. John was kind enough to devote an entire afternoon and evening

to our small team and I am pleased to say that I have a wide range of his wines

available via the Planet Wine website.

Planet Wine offers the widest range of Georgian wines in NZ

Kahka from Tchotiashvili Winery

More recently, I have added the wines of Iago Bitarishvili and his wife Marina, as well as Tchotiashvili. Planet Wine has by far the widest range of premium Georgian wines available in New Zealand now.

While proponents of the natural wine movement may jump at the chance to taste Georgian wines, I am interested in a broader assessment from wine connoisseurs who have honed their senses on more traditionally-made wines. My experience in Georgia proved to me that many vintners producing natural wines in the New World still have a way to go, although improvements in recent years have been rapid.

I have met makers of natural wines around the world whose products I really appreciated. Planet Wine is already representing the Testalonga wines from South Africa, Dave Geyer’s products from the Barossa Valley, and a few wines from our long-term suppliers and friends, Mas Candí in Penedès in Spain.

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...